Functional Programming debunked

What is Functional Programming

Functional programming is a programming paradigm - like imperative programming - that emphasizes on computations being the evaluations of mathematical function. Put simply your functions must be like mathematical functions. The functions must comprise of expressions and not statements(like in imperative style). Expressions evaluate to an outcome or result. Expressions are extremely developer friendly because they lead to very expressive programs.

#Python

3 * 3 # is an expression because it returns 6

if 10 > 3: print "10 is bigger than 3" # is not an expression since it does not return anything

What are the tenets of Functional Programming

There are some necessities to call a programming language Functional. Some are mentioned below.

Functions as First class citizens

This is the single most important property for a Functional programming language. To understand what first class citizen means let’s look into Java. Java being an object oriented language, everything revolves around objects. Fields are objects themselves - they can be passes as an argument to a method, assigned to a variable, returned from a method and so on. However, methods in Java are mere behaviors associated with objects. All you can do with a method is to invoke it on an object. Thus, in Java, fields/properties are First class citizens and methods/functions are second class citizens. In a Functional programming language, functions are first class citizens - they can be passed as an argument to another function, returned from another function, etc. In a gist, everything is a function or revolves around functions in Functional Programming.

#Python

def add(a, b): return a + b

#assigning function to variables(even though assignment is not valid in pure functional style)

func = add

Higher order Functions

Higher order function is a function that takes function as an input parameter or returns functions or does both. This is a very powerful arsenal in functional programming that leads to very minimal code and brings in a lot of code reusability.

Let’s delve with some example. We need a function that takes a list and returns all elements divisible by 2. We use List comprehension for simplicity.

#Python

def divisibleBy2(lst):

return [i for i in lst if i % 2 == 0]

print divisibleBy2([1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8])

So far so good. The above approach is not extensible though. Say, if tomorrow we need to get multiples of 3, 5, 7, etc. We would need to write one function for each. A better approach is to make a generic function that takes two arguments - the input list and a number ‘n’ which is the divisor, and return elements in the list that are divisible by the divisor ‘n’. This works for simple cases.

But this approach wont work if we need complex cases like get numbers that are divisible by both 2 and 3, get numbers that are divisible by 2 and 3 but not by 5. This is where higher order functions shine - functional reusability. We modify our function to take two arguments - the input list and a function(predicate) that takes an Integer as an argument and returns a Boolean.

#Python

def divisibleBy(lst, fn):

return [i for i in lst if fn(i)]

#lambda is for anonymous function

print divisibleBy(range(1, 100), lambda i: (i % 2 == 0 and i % 3 == 0 and i % 5 != 0))

Here we are giving the full responsibility, of what exactly the predicate function should be, to the client that’s using our function. So, it’s very extensible and flexible. All we need is a function that takes an Integer and returns a Boolean - the body of the function could be anything.

Similarly returning functions are also very useful. Lazy evaluation is one of the uses for returning functions.

#Python

def computationallyIntensive(arg):

#do simple tasks

arg1 = arg * 1000 / 250

#inner function

def intensive():

#do intense operation with arg and return result

#return function

return intensive

val func = computationallyIntensive(arg)

#do other stuff

#evaluate func

print func()

Purity of Functions

Functions must always be pure. Meaning they should work solely on the input to the function(and some constants) and not any other parameter to generate the output. The function must be side effect free. That’s it should not do anything other than computing the result from the input arguments.

#Python

def add(a, b): return a + b #pure function

def impure_add(a, b): #impure version

res = a + b

print "Sum of %d + %d = %d" %(a, b, res)

return res

global_var = 100

def impure_add2(a, b): #impure version

if a > global_var: raise Exception()

else: return a + b

There are lot of benefits making functions pure. Some are

-

Since pure functions are side-effect free, we can retry them any number of times since we know that all it’s doing is working on the input to compute the output and not messing around with anything else.

-

Pure functions are referentially transparent. This means we can replace the function call with the actual result. For eg.

add(2,3)can be replaced with 5 since we know that the function will always return 5 for inputs 2 and 3; and iff(x) = x*xandg(x) = f(x) + f(2*x), we can replace g(x) asg(x) = (x*x) + ((2*x)*(2*x))since we know that f(x) will always return x*x and does nothing else. This equatable reasoning makes it easier to reason about the behavior of programs. One other advantage of Referential transparency is the ability to memoize(cache) the result of computations. This is very useful for computationally intensive functions; we can compute the result once and cache it and if this function is invoked again with the same input, we can serve it from the cache instead of computing it all again. We can Memoize the result since we know that the output is going to be the same for the given input. -

Pure functions are less error prone and easily testable, since they are computational contexts themselves and do not depend on external environment.

Immutability

In a pure functional language, data is immutable. Once initialized data cannot be changed. Any modifications to an existing data might involve creating a new copy of the original data. This is not always the case though as we’ll soon see.

Mutable data has lot of issues especially in a multithreaded environment. We need to make sure that multiple threads has consistent view of the shared data, and that threads mutate data in a safe way. Various languages have different approaches to do this - locks, Actor model, STM, etc. Though some of the approaches are better than others, they certainly involve some complicated logic and hence limit scalability. Immutable data, on the other hand, need not worry about concurrency.

Doesn’t immutability also mean performance hit when trying to mutate large data since we need to copy the entire data with the changed state? Yes and no. Functional languages use functional data structures like List(Linked list), Set(Tree based) and Map(Tree based). Even though there are very few functional data structures, they are all very efficient and feature rich. Some of the operations involving functional data structures may not at all need to copy the entire data as the unchanged parts of the structure cannot be modified. Let’s see how this is done on List.

List in functional programming is a Linked list.

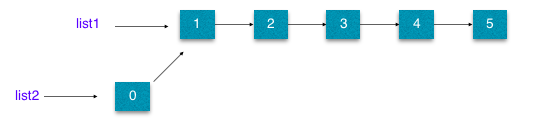

-- In Haskell GHCI

let list1 = [1..5] --list of numbers from 1 to 5

let list2 = 0 : list1 -- a new list with 0 prepended to list1

We might think that list2 is a new copy of list1. However, that’s not the case here.

As you can see from the above image, both list1 and list2 are using the same underlying data as the existing data itself cannot be changed. This approach - unfortunately - will not work on every case. For example it will not work while appending elements to a list, in which case a new copy of the entire list need to be made.

Other tenets

The above mentioned tenets are the pillars of functional programming. There are few others as well.

No Assignments

Functional programming do not have assignments. The value of a variable never changes. The “=” operator in pure functional languages is just for associating a name with a value, and is not an assignment operator. The name can be replaced with its value where ever it’s used. This is not possible with assignments.

-- Haskell GHCI

let a = 10 in a * a -- a is just a name for 10. It cannot be assigned to anything else

Recursions and no loops

There are no loop construct in functional programming. All that can be achieved using loops can be achieved through recursions. One of the reason why loops are not functional is every loop is associated with a mutating state. For example for(int i = 0; i < 10; i++) has a mutating variable “i” that keeps on changing its value in every iteration. Also, there are no concept of loops in mathematics from which functional programming has rooted. Functions in math are represented using recursion if they are self-dependent.

Let’s write the mathematical representation for the factorial function

| 1; x = 0

factorial(x) = | 1; x = 1

| x * factorial(x-1); x > 1

The same in Haskell

-- Haskell

factorial :: Int -> Int

factorial 0 = 1

factorial 1 = 1

factorial x = x * factorial (x-1)

-- or even better using guards

factorial :: Int -> Int

factorial x

| x == 0 = 1

| x == 1 = 1

| otherwise = x * factorial (x-1)

Some languages like Scala, Clojure have limitations on the Thread stack size. So, deeper recursive calls may lead to StackOverflowException in these languages. To overcome this problem, tail recursion is used. Tail recursion is one in which the recursive procedure is ran as an iterative process. The recursive calls are converted to iterative calls by the compiler/interpreter. Only recursive calls that are the last logical statement in a function can be made tail recursive.

//Scala

def factorial(x : Int): Int = {

@scala.annotation.tailrec

def factorial(i: Int, n: Int): Int = { //a tail recursive function

if (i <= 1) 1

else factorial(i - 1, i * n)

}

factorial(x, 1)

}

The following function cannot be made tail recursive since the last logical statement is not the recursive call but the multiplication

//Scala

def factorial(x : Int): Int = {

if (x <= 1) 1

else

x * factorial(x - 1)

}

Lazy evaluation

Most of the pure functional languages prefer lazy evaluation - evaluating an expression only when its results are needed. Lazy evaluation ensures that computations that are not used are never evaluated. Lazy Functional languages typically use graph reduction for evaluation.

--Haskell GHCI

-- The following will fail in a non-lazy language

let list = [1..] -- an infinite list

let a = (1, 2/0) -- divide by zero

Why Functional Programming

As we sifted through various tenets of Functional programming we also looked at the pros of each tenet. In gist, Functional programming is usually very concise, highly reusable, highly modularized, easier to test and debug and a lot less error prone. It’s also extremely scalable because of its immutable nature. Programs written in Functional language are very easy to comprehend since they mostly resemble mathematical functions. Various constructs such as memoization on pure functions can also greatly improve performance and efficiency of the system.

Functional programming languages with features such as algebraic data types, pattern matching and macros makes Meta Programming very easy. Hence Functional Programming languages are ideal for DSL(Domain Specific Languages).

Are purely functional languages efficient

Purely functional concepts can and do bring in some performance issues. For example trying to change the state of a very large data structure - say a large Tree - will incur heavy costs on performance since we may need to make a copy of the entire data structure. Even though Functional data structures - as discussed earlier - are efficiently implemented to reduce the performance cost to a large extent, they still are not very efficient in certain cases. Hence, for all practical reasons, functional languages support certain non functional concepts such as mutability. However, they usually do it in a style closer to functional style or is done isolated from the functional part of the application. For example, Haskell has IORef for mutating variables but they need to be explicitly declared and operations need to be done within a IO Action Monad(a context for impure actions).